A Series on Political Islam and GE15 – Part 5: Mediatised Religion in Malaysia: Islamization by Trolling?

Introduction

The mixture of religion and politics is a staple in Malaysian politics. Islam is of particular interest to many due to its symbolic, social and institutional role as the religion of the majority in a relatively pious and conservative society.

An often-cited reason for Islam’s increased saliency in Malaysian politics is the “Islamization race” between the two major Malay parties in Malaysia, the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) and Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (Pan-Malaysian Islamist Party – PAS). The reasoning is that, as both UMNO and PAS competed to posture themselves as the true “defender” of Islam, they left behind legal, discursive and institutional legacies that entrenched Islam’s prominence in Malaysian social and political life.

The competition normalized Islam as a vernacular of Malay political competition and, as a result of such normalization, more actors sympathetic to Islamism were incorporated into state-building projects that made any effort to seclude the political sphere from religion extremely difficult.

However, the dynamics behind this “Islamization race” is not unchanging. To start, the increased competitiveness in Malaysian politics that began in Reformasi (which really intensified after the watershed 12th General Election [GE12] in 2008 and more so after Barisan Nasional‘s [United Front – BN] defeat in 2018) means it is no longer the UMNO-PAS dyad that determines the course and contours of Islamization.

This is because Islamist actors, as do Malay support, have diffused amongst the many parties and social organizations. Another factor is that the medium upon which discourses and contestations about Islam played out in Malaysia have moved to the online space.

In this article, the focus is on social media, particularly a phenomenon referred to as “Islamization by trolling” that intensified in the past couple of years.

The Trolling: From Subculture to Mainstream

The translocation of politics (or religion) onto social media is not, as some tech people defensively put it, the mere migration of the status quo (or human nature) onto the cyberspace. The medium where social interactions transpired has always been able to exert a disproportionate influence on their forms and practices.

That is why scholars have come up with the concept of mediatization, referring to how the media (be it TV, radio, or social media) transforms “communication forms and relations between the people on the micro level”, as well as the “nets of sense and meaning making on the macro level”. Put differently, the medium defines, determines and arguably distorts the message.

The concept of mediatized religion, therefore, involves understanding religion as narrated, transmitted, visualised, beautified and practised through the algorithms, filters, communities, and connections offered by social media. Indeed, scholars of mediatized religion have indicated that the media have become the primary locus where information, issues and experiences about religion are moulded. Many would say the same for politics as well. Hence, this inter-crossing between social media, religion and politics has to be treated seriously instead of been relegated to an epiphenomenon.

The mediatization of religion and politics also means that both are exposed to some of the more insidious practices in the cyberspace. Trolling is one of them, defined here as “the act of leaving an insulting message on the internet” to deliberately annoy, bait, or provoke the emotional reaction of someone.

Islamization by trolling happens in Malaysia when a party gets exposed, mocked and ridiculed by messages that question its’ “Islamic-ness” on social media and, as a consequence, concedes to that pressure by either backing-down from a less conservative and more tolerant position, or recommitting itself to a higher ideal of creating an Islamic state that has always been a polarizing issue in Malaysia’s multifaith and multicultural society.

The Context: Competition and Revenge

This potent mixture of politicized Islam and trolling is informed by two contexts. The first is that troll culture has pervaded Malaysian politics, as it has elsewhere. According to communications scholar Jason Hannan, “trolling is now an open practice, in which many trolls no longer bother hiding behind fake names and fake pictures, feeling evermore confident to make abusive comments against people they know and do not know alike.”

No longer a subculture inhabited mainly by anonymous users or cybertroopers, trolling is now part of the political mainstream, where “ow

This polarized environment reinforces a tribalist field where everything is fair game for those on the other side. A good example is the publicity surrounding the Super Ring stunt, where former Prime Minister Najib Razak is both the troll and the trolled.

In its almost costless (trolling needs little money to do, nor will it be ostracized socially) and trenchantly anti-intellectual nature, trolling is conceivably the avenue of the lowest barrier for one to participate in Malaysian political life, even if what it reinforces is a kind of thoughtless tribalism that perverts the social and moral fabric of the nation.

Troll pages in Malaysia generally enjoy a massive following, with one dedicated to trolling politicians earning up to 600,000 followers before Facebook shut it down for going against community standards. Malaysians are known to be enthusiastic participants in global trolling campaigns, with its anti-Israel “troll army” enjoying a degree of infamy. What is often left out in these stories are, regrettably, the human stories of trauma and abuse suffered by Malaysians as a result of the rampant trolling.

The second context to consider here is that “Islamization by trolling” happens at a juncture where all the major Malay-Muslim parties in Malaysia have enjoyed power at the federal level. This is a product of the electoral upheaval in 2018 that brought into power the Pakatan Harapan (Alliance of Hope – PH) coalition (along with Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia [Malaysian United Indigenous Party – Bersatu] and Partai Amanah Negara [National Trust Party – Amanah], UMNO’s and PAS’ splinter party respectively). The Sheraton Coup in 2020 also resulted in the Malay-dominant Perikatan Nasional (National Alliance – PN) coalition headed by UMNO, PAS and Bersatu taking over.

In this musical chairs scenario where all the Malay parties have a shot at power, accusing the other for not being “Islamic” enough makes sense because each sees marginal swings in the Malay vote as sufficient to produce an electoral upturn.

PAS is the obvious candidate for such ridicule as it is the party that promises the most within the Islamic agenda. By setting the highest purity standards in all those years lobbying for Islamic rule, these standards have come back to bite them as they got into power. The damage is arguably self-inflicted, considering the ultraorthodox form of Islam PAS champions (at least in rhetoric) is the most contentious to implement in the more urbane and ethnically mixed parts of the West coast of the peninsula. For example, PAS’s protests against international concerts held in Kuala Lumpur strikes many as bizarre, given that it is part of the government.

There is also a motive of revenge behind the trolling. During PH’s rule, PAS (and many others) actively condemned the government as anti-Islam, with Amanah, a relatively moderate Islamist party, most vulnerable to such critique. Thus, once PAS got into power and had to contend with the realities of governing a multicultural society, its foes in PH were more than happy to subject PAS to a taste of its own medicine.

The party was constantly questioned about its commitment to realise the kind of hard-line Islamic rule certain PAS figures, such as its president Hadi Awang, love to expound. In this reading, the trolling is meant to expose PAS’s hypocrisy. One example of this happening is when an Amanah leader raised the issue of Malaysia having a whiskey brand named after a Malay word Timah (tin), which caught fire with another PH politician suggesting that, with that name, drinking the spirit is like “drinking a Malay woman.”

Mocked for having a “Malay” alcohol launched during its tenure, PAS demanded the company to change the brand name, but ultimately relented as intervention from the non-Malay partners of PN successfully put the issue to rest. However, the incident highlights PAS’s unique vulnerability to such trivial challenges of its “Islamic-ness”.

It is not just PH-affiliated

Terms most associated with PAS-trolling include penunggang agama (exploiters of religion), parti lebai, parti ana, and parti Isley. These wordplays that project a stereotype of PAS as a rural, Kelantanese party held by senile ulamas are meant to mock the party’s image as an out-of-touch party obsessed with a kind of unworldly piety, or its hypocrisy where the behaviour of its leaders simply does not match its vaunted ascetic piety. As far as my observation goes, these terms have seeped into Malay popular discourses, signifying how PAS’s longstanding Islamic branding does not shield it from the criticisms of a cynical, even if increasingly pious, Malay audience.

Trolling Ourselves to Ultra-Orthodoxy and a Surveillance Society

Trolling would not be an issue if they are just harmless fun. But it has significant political implications for two reasons.

First, PAS, most vulnerable to such trolling, is no longer a marginal player in Malaysian politics. As of writing, it controls three states and held important cabinet positions prior to the dissolution of Malaysia’s parliament. After the Muhyiddin government collapsed in August 2021, PAS controlled both Minister and Deputy Minister positions in the Islamic Affairs portfolio. Thus, what PAS did in response to being trolled is incredibly consequential.

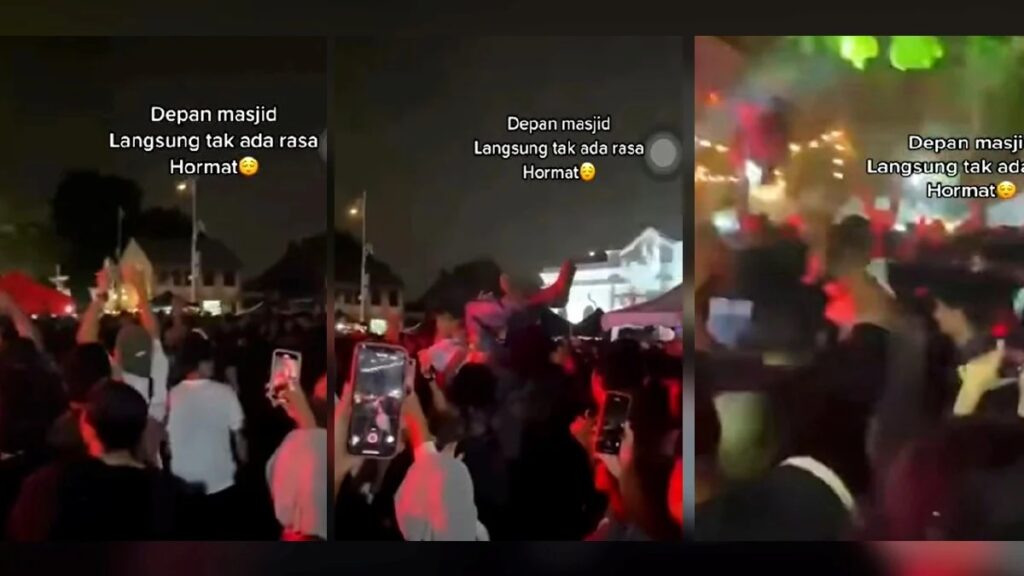

For example, the PAS-led Kedah government has recently decided to ban all open-air concerts and festivals. This reaction came from the pressure built up by PH-supporting social media accounts trolling the Islamist party for allowing a concert in Kedah, although they would have been perfectly normal in PH-governed states like Penang or Selangor. Not only that, the PAS government in Kedah was also trolled for other issues, such as allowing a bodybuilding competition involving female contestants and a Fashion Week.

It is important to note that the holding of these events is nothing out of the ordinary. As a BN-governed state for most of its history, Kedah has a formidable PAS presence but was never subjected to the kind of religio-moral policing found in states like Kelantan and Terengganu. Thus, banning concerts in Kedah should be considered as a kind of reactionary Islamization undertaken by PAS when it found itself defenceless against such trolling tactics.

It is Islamization because the trolling pushes PAS towards stressing its “Islamicity”, as seen in this post where PAS claimed that it was not against concerts, just that they had to follow sharia guidelines, such as maintaining strict gender segregation and knowing “limitations”. What is left unsaid (and probably unspeakable) is the rights of the non-Muslims who must have found it unfair they had to follow religious codes that are not their own. Also, if PAS could be trolled into submission whenever it seemed to be making some progress, however minor, from its previous conservative stances, the “inclusive-moderation” hypothesis that claims that Islamists tend to moderate when they come into power for reasons of pragmatism may be undermined by the trolling.

The second implication is that trolling almost always drives Malaysian politics in a pro-orthodox, conservative position if the matter involves haram/halal considerations. Because the universe of trolling actively disincentivizes and discourages “lengthy, detailed disquisitions” in favour of “short, biting sarcasm”, it almost always forces the trolled party to err on the “safe” side just to stop the hectoring.

In Malaysia’s increasingly conservative religio-political environment, the safe option means more banning and less tolerance. While the spotlight is placed on PAS, what is really being policed by these trolls is the personal, cultural and religious rights and freedoms of Muslims and non-Muslims alike. The true tragedy here is that the trolling may have come from citizens who lived outside of these PAS-governed spaces; people who can still earn a livelihood and personally enjoy those freedoms denied by PAS.

The fear of inviting abuses from the trolls also closes off the discursive space for careful deliberation. This means those directly impacted by the banning (such as the event vendors, Malay-Muslims who hold a more relaxed attitude towards these events and non-Malay, non-Muslims who saw such banning as existential to their religious and cultural rights) are shut out from the debate. The unidirectional manner trolling is leading Muslim politics in Malaysia (i.e. in a majoritarian, authoritarian and conservative trajectory) can be seen from the fact that anyone who disagrees with PAS’s bans cannot troll PAS into reversing those decisions.

Trolling has always been about highlighting the inconsistency of PAS, not its intolerance. This means that the more trolling becomes the dominant form of discourse surrounding Islam’s position and praxis in Malaysia, the harder it

Interestingly, “Islamisation by trolling” works in the opposite way of the UMNO-PAS Islamization race mentioned in the beginning. The Islamization race is about “raising the bets” as PAS and UMNO challenged each other through what they do. If PAS did Islamic policy A, UMNO would follow up with Islamic policy B.

But “Islamization by trolling” does not require its interlocutors to actually do something. Rather, it is just about trolling your opponent for doing, or not doing, something without showing any ideological commitment of your own, nor do you have to shoulder the risk of doing or not doing the thing in question.

For example, PH-supporting social media accounts have trolled PAS for not including the RUU 355 bill that may pave the way for hudud implementation in its manifesto. Forced to respond, PAS retorted that it did not include RUU 355 because the party was already doing all it could to expedite the bill. In other words, just as PAS was trying to settle for a less dogmatic positioning, the polarizing Hudud agenda was hauled back

Yet, it makes no sense that PH should troll PAS for RUU 355 because no PH parties would touch the issue with a ten-foot pole. After all, a significant portion of their urban and non-Malay constituencies are against it. It is almost as if the Democrats in the United States are pressuring the Republicans to be tougher on banning abortion, which is virtually unthinkable because their progressive base will call them out. But in Malaysia, while there are some pushbacks from PH supporters against these kinds of trolling, they persist, nonetheless.

Looking Ahead: Will It Stop?

Whether such trend will continue really depends on why the PH-leaning crowd does it. If the motive is revenge, then they may stop after realizing moving the Overton window on issues of religious propriety will do them no good. PH is already widely seen as too liberal and secularist, so even if the hypocrisy of PAS is exposed, that does not mean the conservative Malay votes will flock to PH. Plus, disillusionment towards PAS does not necessarily entail a subsiding of the forces of Muslim majoritarianism in Malaysia. Voters may just end up choosing an even more puritan or extreme party. The choice is definitely there as Islamist actors fragment and proliferate.

Trolling will not increase PH’s appeal amongst the conservatives because it makes a case for social intolerance instead of multicultural flourishing. Some PH members have raised the radicalizing effects of such a strategy, but they seem to be in the minority. There are, of course, other reasons for the continuation of the trolling. As mentioned, trolling involves little cost and risk, so the incentives to do it and inflict harm on your opponent are always there. Furthermore, whereas its anti-corruption messaging has battered BN considerably, with PAS PH cannot seem to find an opening for attack other than the hypocrisy angle. In fact, the anti-corruption platform may have boosted PAS’ appeal. PAS leaders have campaigned that it is “cleaner” because, unlike PH and BN, its leaders have no pending court cases.

Lastly, a most uncharitable read for the trolling activism is that some quarters within PH actually harboured hopes for a conservative “Islamic” agenda but does not want to do it themselves as part of a coalition enjoying substantial non-Muslim support. This is not unthinkable. On issues concerning sexuality rights, liberalism, non-Muslim rights to alcohol consumption and apostasy, PH-leaning Islamists from groups like the Angkatan Belia Islam Malaysia (Muslim Youth Movement of Malaysia – ABIM) and Pertubuhan IKRAM Malaysia (IKRAM) may hold views that are closer to the conservatives than the liberals, even as they are not vocal about it. To be sure, having disagreements within a broad-tent coalition is nothing special. But to push for a social and political agenda without even trying to convince your core constituency, namely the liberal and non-Malay voters, strikes one as being disingenuous.

That is the peril of resorting to trolling as a kind of political activism. It does not increase accountability (because trolls often do not have to come clean of their positions) but surveillance. It subjects everyone to an impossibly high moral standard without offering the space where these standards can be renegotiated amongst different social groupings. It creates a situation where the biggest bully wins and moderation loses.

Part 1: Islamists vs Islamists in GE15

Part 3: The Malay-Muslim Politics and Malaysia’s GE15

Part 4: The Sustainability of the Next Islamic Initiative in Malaysia