Introduction

The Thai Government was hoping to secure a ceasefire with the Patani Malay separatist rebels for this year’s Ramadhan. However, after over two weeks since the start of the holy month, the two sides still have yet to find middle ground.

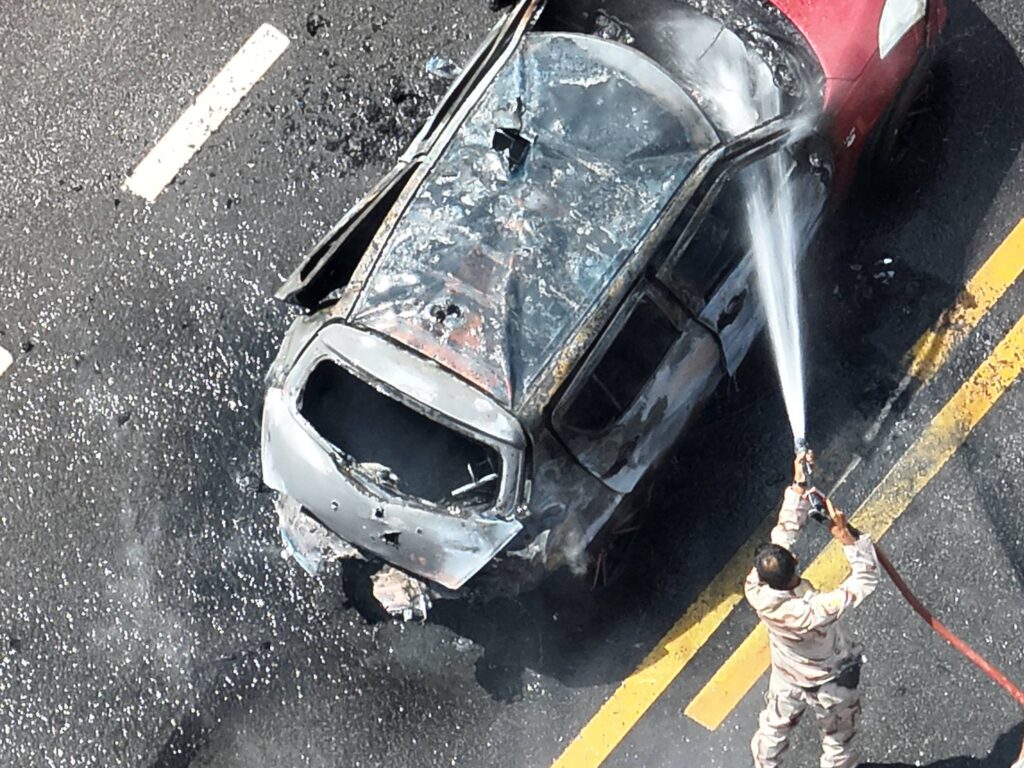

Worse, violence has not only spiked – the recent attacks have been extremely daring. As seen on 8 March 2025, a group of about 10 combatants raided the compound of the Sungai Kolok District Office in Narathiwat just before midnight, killing two and wounding seven security officials in a brief but fierce gunfight.

The combatant arrived in two vehicles, one of which was packed with explosives, parked near the district office building. It was set off shortly after they retreated from the vicinity. The same evening, in Sai Buri District of Pattani, a smaller explosive lured Paramilitary Rangers to the scene, where they were hit with a much more powerful bomb. Insurgents commence fire immediately upon explosion, killing three Rangers at the scene. This was not an isolated incident. Earlier in the week, suspected insurgents threw pipe bombs at security officials near the train station in Yala, wounding four bystanders. And on Monday morning (March 17), a security officer from the Ministry of Interior barely survived a blast from a bomb that was hidden underneath her personal vehicle that went off as she was driving to work. Words have been out for some months now about rebel forces urging MOI’s security officials, locally known as Defense Volunteers, to quit their job and to refrain from acting as spies or agent for the Thai security apparatus.

These incidents, caught on CCTV from various angles, reinforced the understanding that insurgency is a form of communicative action in which a non-state actor uses violence to send political messages to the state security apparatus.

Indeed, the Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) has not been pleased with the Thai government’s foot dragging with the peace negotiation. In December 2024, Nikmatullah Bin Seri, the head of BRN technical team, issued a public statement saying the group was prepared to walk away from the process and take back their commitment to negotiate under the Thai Constitution if Bangkok is not serious about the talk. The peace process was supposed to resume once a new government came to power after the 2023 general election.

The following month, Thai Defense Minister Phumtham Wechayachai called on all relevant agencies to draft an “actionable solution” to resolve the conflict. Days later, Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra made her first visit to the far South. Incidentally, she visited the Thamvithya Mulnithi school, where several BRN political figures and the chief negotiator, as well as the late spiritual leader of the movement and the Patani region, Sapae-ing Basor, had worked as teachers and principal before fleeing Thailand to avoid arrest.

Phumtham’s directive and the PM visit may suggest that the government was giving in to BRN’s demands. But in fact, Bangkok was setting rigid terms for future talks. According to a government source, Phumtham has demanded that BRN curb their violence before he would appoint a negotiating team. He is also considering doing away with foreign mediation, which would mean an end to all back-channeling, and axed the position of the five international conflict experts who function as observers for the high-level talks. Malaysia, the designated facilitator, will be the sole mediator for the talks, according to one Thai official who spoke on condition of anonymity.

It is not clear if Phumtham will scrap the Joint Comprehensive Plan Toward Peace (JCPP), the so-called road map for peace. Thailand and BRN, with the help of foreign NGOs and Malaysia working in separate and often competing tracks, spent the past three years going back and forth on the JCPP. They identified three items to be on the negotiating table: reduction of violence, public consultation, and a political solution to the conflict. Specific details are to be negotiated in the following phase.

BRN leaked the draft of the JCPP to the public early last year to test the water; the result was a big stir among government security officials and the military, who never liked the idea of talking to the rebels in the first place. They still think military option is the best way forward.

Because of the outpour of criticisms from the public and top government advisors, the Thai negotiating team was badly isolated; they were accused of giving in too much to the BRN. What Phumtham does not understand is that for the BRN, the peace process is the beginning of a very long journey that will not rest until the movement achieve either independence or a form of “self-government”. Under the latter arrangement, sovereign remained with Bangkok but regional Parliament makes the law for this historically contested region. According to a report released by The Patani on the peace process, BRN maintained that even under a “self-government”, the people of Patani must retain the right to succession.

These are tall order, indeed, considering that after two decades of off-and-on peace initiatives, Thailand has never permitted the talks to move beyond confidence-building measures. Even with direct engagement with BRN, the one group that control virtually all the combatants on the ground, Phumtham continue to sound like a broken record – suggesting that the government is still doubtful of working directly with BRN or if BRN is truly the party that the government should work with. While this suggests a need for the government to verify that it is talking with the right people, such verification may not amount to anything in light of the government’s high level of distrust to BRN.

Stalled Negotiation

In line with past practices, the Thai side – remnants of the now-defunct Peace Dialogue Panel, the official negotiators – tried to push for a ceasefire during this year’s Ramadhan, which started on 1 March 2025.

Malaysia’s facilitator for the peace process, Mohd Rabin Basir, tried hard to help the Thais push this request through but was not able to do so. This was because BRN refused to budge on their demand that the ceasefire include a monitoring mechanism by international peace and conflict experts and that local civil society organizations be given a role in observing the process as well. Other demands include the release of BRN prisoners and the appointment of a negotiating team for the peace talks.

Observers of the peace process said they are not surprised why BRN refused to give in to the Thai government’s call for separate unilateral ceasefire during the month of Ramdan. First, said Artef Sohko, president of The Patani, a political action group dedicated to the right to self-determination for the southern people, Thailand has always tried to use the reduction of violence for short-term political gains.

“BRN can see through Thailand on this and that’s why they are not going along with it this time around,” Artef said.

BRN still recalled how the Thai Army belittled their unilateral ceasefire during the Covid-19 pandemic following a call for a global ceasefire from the UN Secretary General António Guterres. It was an opportunity missed as the Thai side could have reciprocated BRN’s gesture of goodwill and build on it. Instead, the Thai Army in the far south unleashed search and destroy operations, taking down combatants who were laying low in and around the home village in a series of lob-sided standoffs.

What was astonishing in the mind of the many security officials was the fact that, despite being outnumbered by 60-70 to one, all but one of the combatants chose death, or rather, fight to death, instead of surrendering, even though their chances of making it out alive were slim to none. A total of 60 BRN combatants were killed in the standoffs during this window.

Despite the grave disappointment because the Thai Army’s refusal to stand down, BRN did give Thailand the benefit of the doubt. The agreement for Ramadhan 2022 was pretty straightforward – the Thai military vowed not to go after cell members, while BRN agreed not to carry out attacks during the Muslim holy month and through Visakha Bucha Day, a Buddhist holiday observed this year on 15 May. A bigger leap of faith was the move to declare all mosques in this region a sanctuary where combatants could meet their family members during the last 10 days of Ramadan, which ended on May 1.

It is Not (Just) Religion

Local activists who observed the conflict warned against bringing religion into the equation could complicate things because the root causes of this conflict are political in nature as it has to do with the Malays’ rejection of Thai policy of assimilation that comes at the expense of their ethno-religious identity. For Muslims in this historically contested region, it is already a big turn-off when this predominantly Buddhist state tries to use Ramadan for its political gain.

Every now and then, Islamic religious leaders have been called upon to issue fatwa, or religious edict, to condemn the rebels on religious grounds. Needless to say, this effort made Muslim clerics in this region extremely uncomfortable as it would pit them against the separatist combattants. Moreover, separatist insurgency between the Thai state and the Malays of Patani does not have the support of the Thai Muslims who live outside the Malay-speaking South.

It has always been the Patani Malay cultural-historical narrative, not religion, that keep on producing generation after generation of fighters. While the banner of the struggle is rooted in Malay nationalism, words and actions are often expressed in religious terms. All Patani Malay fighters are buried as shahid, or martyr, for example. For the Malays of Patani, identity and religion are two sides of the same coin. Thus, when Thailand pushed through its policy of assimilation that required the Malays to deny their own identity and embrace the Thai one, they rejected it violently.

Today, the battle over the narrative between the Malay activists and the Army has reached the court. Patani Malay activists feel that they should be able to talk about referendum in a public forum, while the Army insisted that such discussion is not negotiable. Sadly, said Artef, the Army appeared to have the support of the so-called pro-democracy movements in Thailand when it comes to Thai nationalism.

While many may support the idea of a separate Malay Muslim state, no one would openly say it publicly as it would invite nasty retaliation from the Thai government. So far, more than 40 youth activists have been charged by the police, at the request of the Army, with instigating a separatist state because they had used words like “Bangsa Patani”, “referendum” and “shahid” in relation to the conflict resolution and the combatants killed in a gunfight against the Thai security forces. In the local context, Bangsa can be translated as community, nation or even narrative.

History Stings Still

While Ramadan carries a religious significance for Muslims worldwide, the Malays of Patani are reminded of the Tak Bai massacre – an incident in October 2004 – in which 78 young Malay Muslims were smoldered to death on the back of Thai military trucks; seven others were shot dead at the protest site.

However, just a month before the 20-year statute of limitation expired, a Narathiwat court decided to try to cases on murder charges against 14 men linked to the death of the unarmed demonstrators. Officials were not able to bring any of the accused to the court and the case was permitted to expire. For some, it was their last attempt for justice. For others, it was an opportunity for some kind of closure with the hope that the country could move on as a nation. Obviously, that did not happen.