Introduction

The Democratic Action Party (DAP) has long been a dominant force in Malaysia’s political landscape, particularly among the urban and ethnic Chinese electorate.

Founded in 1966, it advocates a centre-left, social democratic platform and was historically associated with the “Malaysian Malaysia” slogan – championing equal rights regardless of ethnicity.

For decades, it functioned as a principal opposition force against the long-ruling Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition and, more specifically, against the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA), BN’s Chinese-based component party.

DAP’s confrontational stance and vocal defence of Chinese education and civil liberties earned it both staunch support among Chinese voters and criticism as being anti-Malay or anti-Islam.

In recent years, however, DAP has transitioned from its traditional oppositionist posture to a key partner in Malaysia’s ruling coalition under Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s Madani government. Meanwhile, its recent internal election signifies DAP’s evolving ideological identity and strategic repositioning, particularly in relation to ethnic representation and governance.

New Election, New Era

DAP concluded what is arguably the most intense internal party election in its history on 16 March 2025.

There are three noteworthy points to be analysed.

First, the results mark a symbolic end to the era dominated by the Lim family, signalling a generational transition in leadership and political strategy.

The most notable development was the removal of Lim Guan Eng from his position as national chairman—a shift popularly described within the party as “sending off the god”.

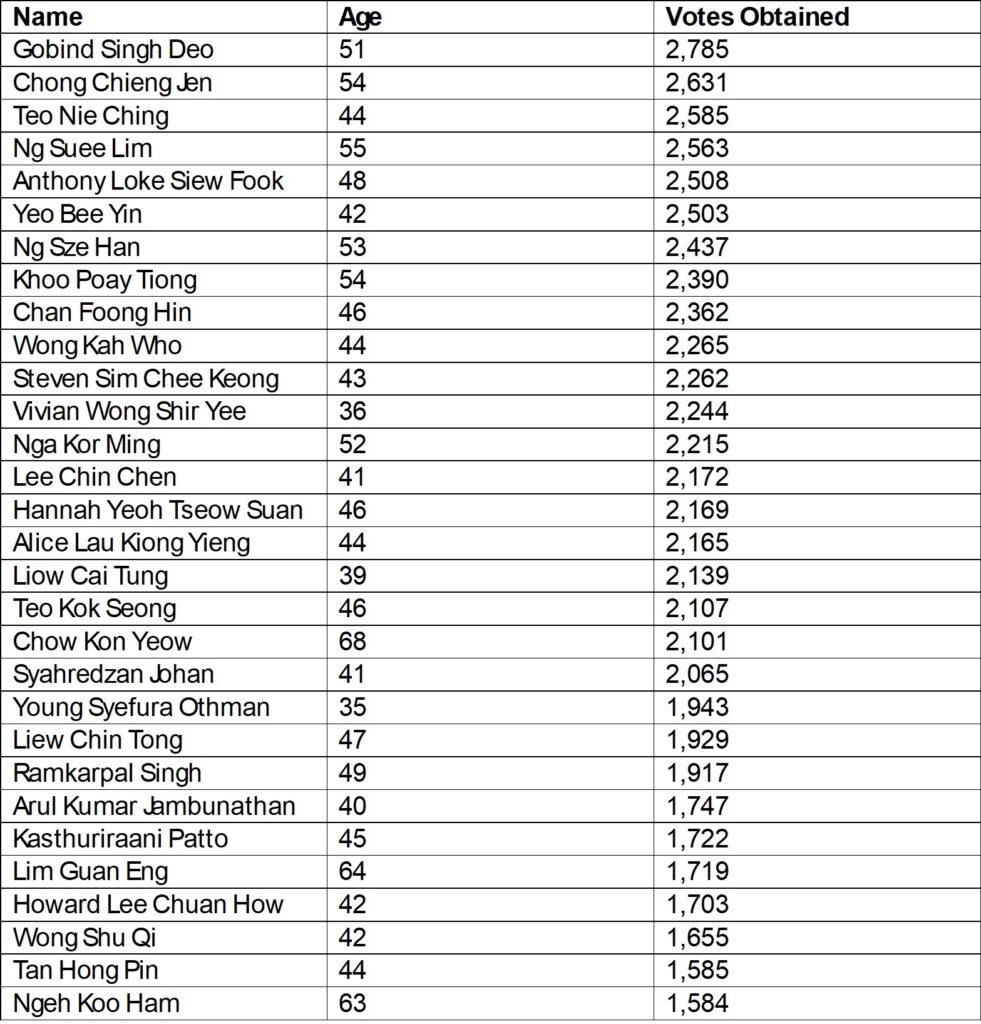

Lim, who served as secretary general from 2004 to 2022, barely retained his seat in the 30-member Central Executive Committee (CEC), placing 26th out of 30. His sister, Lim Hui Ying – Malaysia’s Deputy Finance Minister – failed to secure reelection despite the existence of a female candidate quota.

Other close allies of the Lim faction, such as Teresa Kok (MP for Seputeh, Kuala Lumpur Territory) and Lim Lip Eng (MP for Kepong, Kuala Lumpur Territory), were similarly defeated.

In the run-up to the election, the Lim family launched a “Kit Siang’s birthday tour” to galvanise grassroots support for Guan Eng’s continued leadership—a move interpreted as a pre-emptive bid to maintain influence amid waning support, yet it does not seem to be working out in favour of Lim’s family.

Gobind Singh Deo, son of the late party icon Karpal Singh, received the highest number of votes for the second consecutive election and was appointed as the new party chairman.

The secretary general role remains with Anthony Loke, who is also Malaysia’s Minister of Transport. He has formally succeeded Lim Guan Eng in 2022.

This leadership reshuffle effectively ends the Lim dynasty’s hold over the party. For context, Lim Kit Siang, the family patriarch, served as secretary general for 30 years and as chairman for an additional five years until his retirement in 2022.

Table 1. List of the newly elected CEC members, their ages and the votes obtained

Second, the election outcomes do not only represent a shift away from the Lim family but also indicate a broader generational and ideological renewal within the party.

The new CEC is largely composed of MPs or State Assembly representatives in their 30s and 40s, many of whom grew up during DAP’s rise to national prominence and tasted political power during the party’s brief stint in government (2018–2020).

This younger cohort is more open to engaging Malay voters directly and is working to project a more inclusive, multiracial image. Their multilingual capabilities and cross-ethnic social networks enhance DAP’s strategic goal of becoming a truly Malaysian party.

The rebranding is particularly significant in combatting long-standing accusations of Chinese chauvinism and in adapting to Malaysia’s deeply communal political terrain.

Third, a significant milestone in this party election is the inclusion of two Malay leaders – Syahredzan Johan (MP for Bangi, Selangor state) and Young Syefura Othman (MP for Bentong, Pahang state) – in the CEC. They garnered 2,065 and 1,943 votes, respectively. Syahredzan was appointed as one of the party’s four vice chairmen, while Young Syefura became assistant publicity secretary.

In previous party elections, Young Syefura was the sole Malay representative in the leadership. The dual election of Malay leaders signals DAP’s strategic recalibration: it recognises that it could no longer rely solely on urban, Chinese-majority constituencies. As many as 96% of Chinese voted for DAP in the 2022 general election, whereas only 18% of Malays voted for DAP.

While no official data exists on DAP’s Malay membership, Syahredzan has already announced efforts to recruit more Malay members and voters. These appointments reflect the party’s understanding of the demographic and electoral imperatives of a Malay-dominated society—and an electoral system that rewards broad-based, interethnic appeal.

Between Muting and Maturing

As DAP transitions to a new generation of leadership, the party faces a delicate balancing act: sustaining the loyalty of its traditional Chinese support base while expanding its appeal among Malay and other non-Chinese voters. This requires not only a shift in rhetoric but also demonstrable commitment to inclusive governance and coalition pragmatism.

Moreover, the party’s entry into the unity government has already been met with mixed reactions, particularly from its core Chinese electorate. While the party continues to enjoy overwhelming Chinese support, it has been notably subdued on issues historically central to its platform—such as Chinese vernacular education and minority rights. Critics have even labelled it “a silent party”.

Hence, the party’s current dilemma is how to avoid becoming an “MCA 2.0”—a euphemism for being seen as compliant or ineffective within a Malay-majority government.

Being in power means DAP can no longer simply critique from the sidelines; it must deliver tangible results. If it fails, it risks losing credibility and electoral support.

Nevertheless, the prospect of Chinese voters shifting back to MCA remains unlikely. A more probable outcome would be voter apathy and abstention.

The deeper challenge lies in how DAP balances its “Malaysian Malaysia” ideals within the constraints of Malaysia’s racially stratified political landscape. Its transition from antagonist to conformist illustrates the compromises required under coalition governance. Whether DAP can maintain ideological clarity while expanding its electoral reach remains to be seen.

In short, DAP’s future depends on whether it can reconcile its activist roots with the compromises of coalition politics without losing the ideological clarity that once defined it. If it can achieve this balance, DAP may yet complete its transformation into a truly national party with multiracial appeal. If not, it risks fading into the same irrelevance that befell the very parties it once opposed.